MODENA,

ITALY

Modena

lies between Venice to the northeast and Florence to the southwest.

This puts it in the "northern" Italian locale, where

innovation was slow, and tradition held fast. There was some

independence of thought, though,

regarding design, but not a lot. Yet the fact that it was the

townspeople who insisted that a new Cathedral be built - without even

having a Bishop on the job - seemingly represents the first such

instance of civic will in the region. This should give some of us

today the incentive to speak out and speak loud when architecture is

not what it should or could be.

An

existing Cathedral was in very poor condition in the 11th

century, and even though there was no bishop, the townspeople decided

to build a new Cathedral, commencing in 1099. The architect was

Lanfranco. Consecration took place in 1184.

The

Cathedral of Modena is not mentioned to any great length in most

texts, but small references occur on a steady basis, and Modena

suddenly appears as a typical northern Italian Romanesque church.

Its town Internet site calls it "one of the more important

Italian Romanesque creations." Let's take a look.

The

western façade is divided into three parts corresponding once more,

in good Romanesque fashion, to the interior layout.

There

is a 12th

century rose

window.

An

interesting bit of research would be to find the first rose window in

the entrance façade of a Christian church.

The

rose is said to be symbolic of the Virgin Mary, and might be the

reason for the name of the round opening. Another thought could be

that the multiple divisions in the windows resemble rose petals.

Directly

below the rose window is a highly decorative sculptured Portale

Maggiore (main

door) by Wiligelmo, who also created four major stone carvings.

Actually, references to the Cathedral remark on the collaboration and

joint efforts by both the architect and the sculptor; again, the

integration of art and architecture through the efforts of artist and

architect.

Sources indicate that the sculptor did not merely provide

accessories for the Cathedral, but created an integral and essential

part of the building.

The

south façade shows stonework and marble designed by Lanfranco.

Apparently, some material was borrowed from Roman buildings in the

city. There are applied columns culminating in arches, which in turn

have three open arches within. If this looks familiar, it should.

We saw very similar treatment in the complex at the Cathedral of

Pisa, when we mentioned the Pisan School characteristics. And back

in Caen, the Abbaye aux Dames as well as the Abbaye Aux Hommes had

similar characteristics.

On

the north

side, the entrance is known as the Porta

della Pesheria.

The arched opening contains sculptures of sacred subjects, the

months of the year, and bestiaries.

This integrated art was undoubtedly intended to impart communication

to people who could not read.

The

apse also features the applied columns culminating in arches, with

their three smaller arched openings within.

While

the exterior was covered with stone and some marble, the interior is

of brick construction, and conceivably manifests a Lombardian

characteristic, in that clay is plentiful in Lombardy, as opposed to

the abundance of stone in Tuscany.

What

we seem to have is a conglomeration of materials and effects. Some

historians state with authoritarian conviction that there are

specific and definite characteristics for each Romanesque region of

Italy - the North, Central, and South. These are the basics:

Northern

Italian

designs featured flat, severe entrance facades masking the interior

nave and aisle configurations, and those exteriors were rough, and

without marble facing. Internally, the naves had ribbed vaults.

Central

Italian

designs sported classic details (proximity to Rome, of course), and

multiple arcades one on top the other.

Souther

Italian

designs (especially in Sicily) featured Byzantine, Muslim, and Norman

details, while stripes and stilted pointed arches dominated.

In

general the basic ingredient of Italian architecture was

horizontality.

Verticality, or a reaching to the heavens, manifested itself in

free-standing bell towers, known as campaniles.

These

towers abounded, often serving as watch towers, but just as often as

symbols of power (and money). Baptistries were also free-standing.

The

above are pure generalities, often being exceptions as opposed to

rules. As we're already seeing, materials slipped through these

"borders".

Back

to Modena where the walls are heavy, with minimal openings,

resulting in a very dark interior.

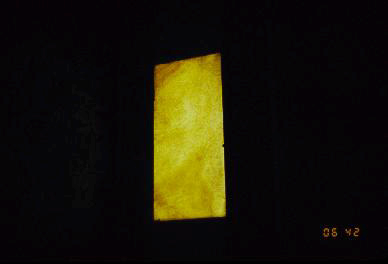

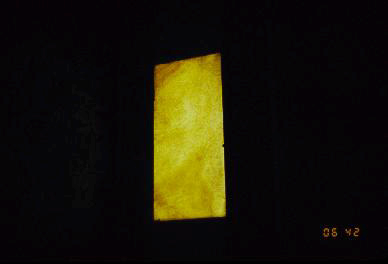

The

windows are of alabaster,

and are translucent, admitting a golden glow. Many churches in this

time frame - the Middle Ages - used alabaster instead of glass. What

ever happened to the abundant use of glass in Roman times?

Most museums of Roman Antiquity exhibit large glass vases, goblets,

and pitchers, which would indicate

certainly,

that if glass was so readily available and extended in size, then it

would have been used for windows. I have

been told in museums and in Medieval buildings that glass had become

very expensive – could there have been an OGEC (Organization of

Glass Exporting Countries), which would have driven up the price of

glass? Please

explore.

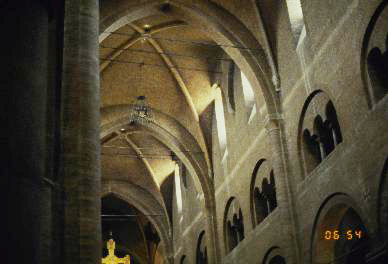

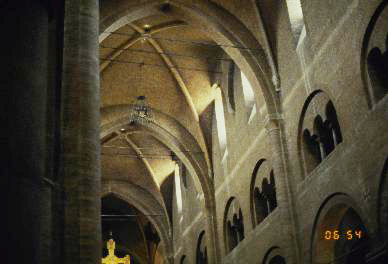

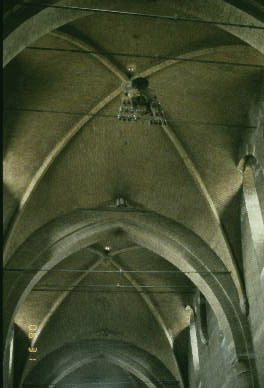

The

ceiling of the nave shows diaphragm

arches

dividing

the nave into bays. Those arches are original, and a wooden ceiling

and roof construction were replaced in the 15th

century with brick vaults, showing a quadripartite design.

The

nave features a double

bay

system

with Corinthian capitals so authentically done that some classical

scholars thought they were of Roman origin. Here we have a touch of

the Florentine school, with its Roman detailing - so we continue to

see a potpourri of ingredients. Dogma just doesn't work in

architecture - it's in the eye of the beholder. The beauty of the

carving

of the podium is attributed to Wiligelmo,

the sculptor. The unusual placement, well within the nave, certainly

brought the priest closer to his congregation, yet a part of that

congregation would have their backs to the speaker. Try

to research the history of what became fairly standard in many

religious structures – the centralized placement of the podium.

There

is a real three-part triforium

gallery

above. I say "real" because though triforium was the name

used to describe the gallery itself, based on early constructions,

you will often find just two arches within the one bay, and

occasionally four.

Here

we can see three!

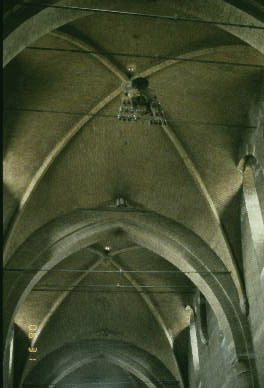

The

vaulting features a perfect example of a quadripartite vault.

The

Cathedral has a major campanile, better known locally as the

Ghirlandina Tower.

It

soars skyward beside the cathedral, on the north side. Almost 90

meters high (290'), it is a combination of two architectural styles:

the square base section is the same age as the cathedral and is in

Romanesque style, while the octagonal and pyramidal upper parts are

later and clearly Gothic in character. Work on the upper part began

in 1261 and was completed in 1319. The tower was designed by Arrigo

da Campione.

The

tower known as “Ghirlandina,” perhaps takes its name from the

two rows of garland-like balustrades which crown it, is viewed by the

people of Modena as the symbol of their city. This is no coincidence:

although this fact is no longer retained in the collective memory,

the Ghirlandina did not only have the religious function deriving

from its status as cathedral tower, but was also a defensive tower

used to store important civic documents and charters.

A

bit of comic relief, which is going to sound like a contemporary frat

house prank, but here's the scoop. The tower is tied to Modena's

identity with one important symbol that is in a way still preserved

in the first room of the Ghirlandina: it is a wooden bucket which is

actually a kind of trophy stolen from the Bologna army by the Modena

forces during the war between the two cities in 1325. It provided

the inspiration for the mock heroic poem written by Alessandro

Tassoni in 1622, entitled "La secchia rapita." or "The

Stolen Bucket." The monument to the north of the Tower,

overlooking the Via Emilia, is dedicated to Tassoni. Every so often,

the bucket returns to the headlines when young people from Bologna

stage an attempt to steal it back again (I warned you about this).

However, the bucket in the tower is only a copy, since the original

is stored in the Palazzo Comunale.

On

a very sad note, in the Piazza della Torre, between the monument to

Tassoni and the Ghirlandina, a small plaque known in the local

dialect as "Al tvajol ed Furmajin" is dedicated to the

memory of the eminent Jewish publisher Angelo Fortunato Formiggini,

who committed suicide by flinging himself from the Ghirlandina in

protest against the racial laws during the Fascist period.

It

isn't just local pride, it's really true that the Cathedral of Modena

is one of the high points of the Italian Romanesque period.

©

Architecture Past Present & Future - Edward D. Levinson, 2009